Moondust: a vital resource for the exploration of space?

It is hard to imagine, but it has been almost 50 years since a human being set foot on the moon. The last time man personally visited Earth’s satellite was in 1972, the year when the Watergate scandal caused president Nixon to resign and the first portable calculators were introduced on the market. However, interest in the moon is growing again. NASA’s Artemis Program aims to return to the Moon by 2024, as a first step to set up a sustained human presence there. And a lot of serious research is being done to make that possible. NPT had a talk with Beth Lomax (UK) and Alexandre Meurisse (F) from the European Space Agency (ESA) in Noordwijk, who did significant research on the extraction of oxygen from lunar soil.

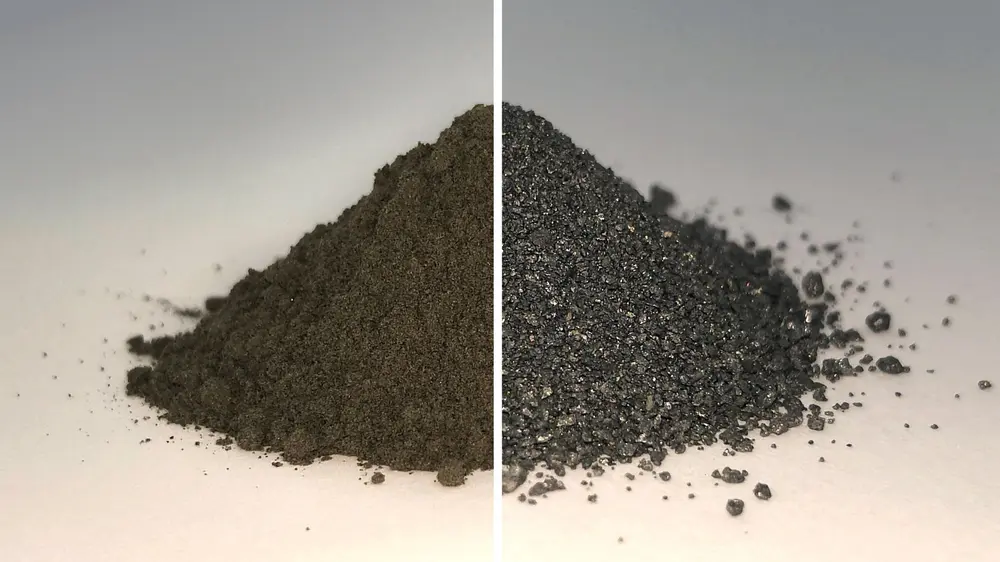

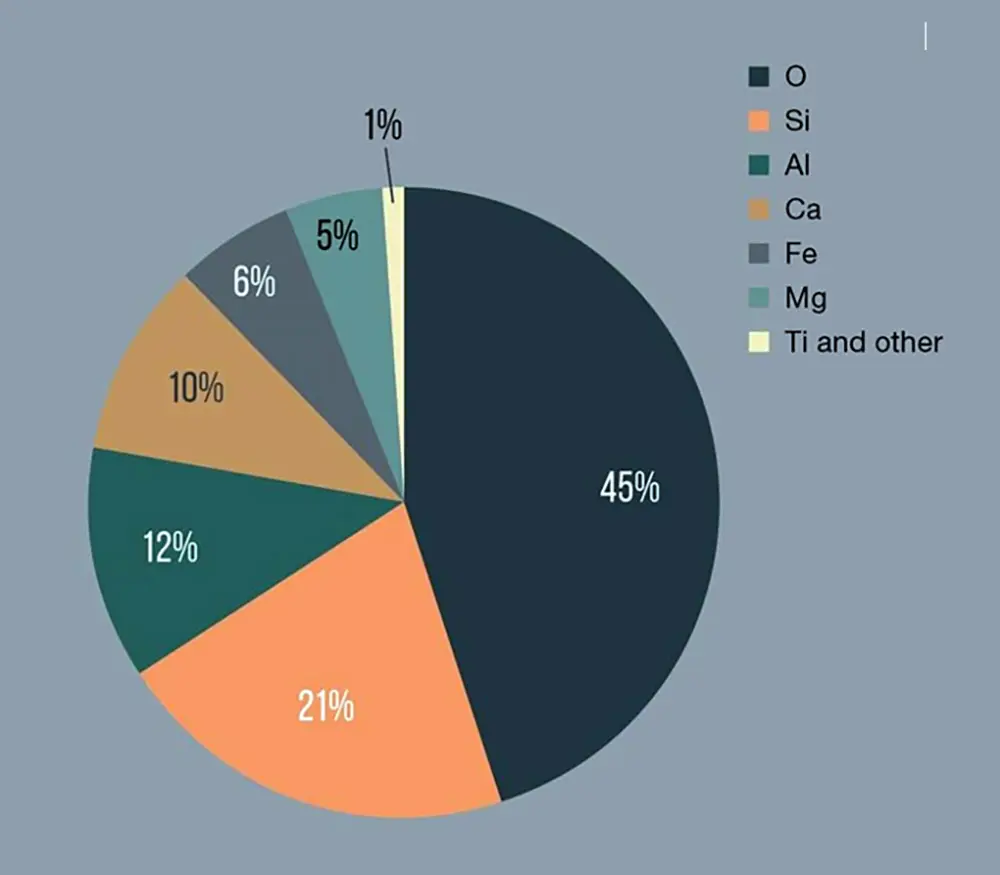

Both of them are young, even budding scientists (Beth just finishing her PhD, Alexandre working at ESA as a postdoc), but they are already enthusiastically involved in the new ‘space race’. “I have been studying the composition and structure of simulated moondust for a long time,” Beth says. “Moondust is quite interesting as a source of oxygen, but - as you can imagine - the real stuff (regolith) is far too rare and expensive for experimental purposes. So we need an artificial substitute that comes as close as possible: its minerality, the chemistry, particle size distribution etcetera. So there was a research initiative here, and we have been working together at trying to extract oxygen from our fake moondust.”

"There are two different methods to extract oxygen from our fake moondust"

Two processes

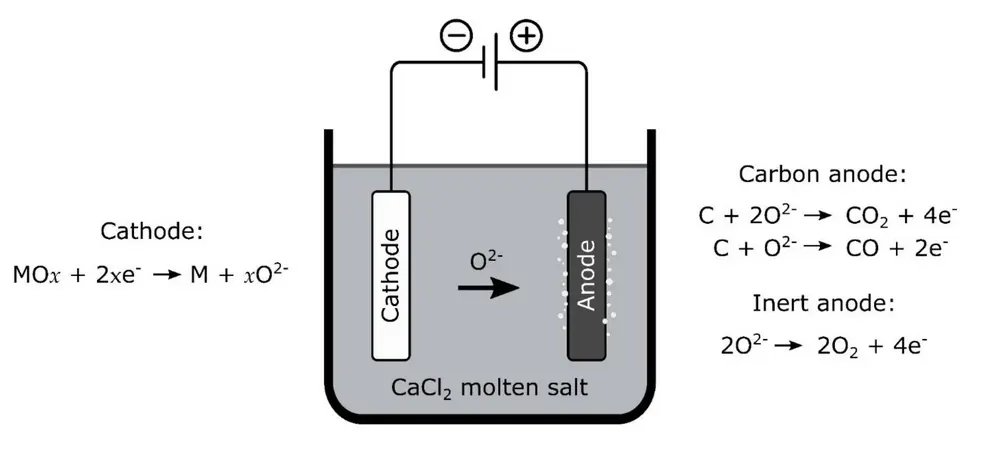

“Basically,” Alexandre explains, “there are two different methods to get the oxygen out. You can reduce the metal oxides by heating them with hydrogen or methane, or by electrolysis in a molten salt bath. Both are pretty well-known industrial metallurgical processes on earth. Silicon, for instance, is produced by pyrolysis: heating the oxide (silica) with carbon.”

Beth Lomax: “But in the lunar context, the most important thing is that all of these processes happen at more than 900°. And to get a good yield in a reduction process, you have to go up to 1.600°, which creates all kinds of problems. You need methane or hydrogen, and an enormous amount of energy. The power you need for the electrolysis is just a fraction of the energy required to keep the system hot.”

Efficience and sustainability

Meurisse provides the background: “The whole idea of extracting oxygen on the moon is based on efficiency. The oxygen produced is not just meant to be used in a future base on the moon, but also to provide the oxidiser needed to burn rocket fuel – on trips to Mars or back to earth. Remember that the Moon’s gravity is only about 1/6 of the gravity exerted by the earth. And the weight of the oxidiser is a large part of a rocket’s take-off mass. So in principle it makes a lot of sense to extract the oxygen from the minerals on the Moon”

“It’s also part of a general effort to make space travel more sustainable in the long term,“ Beth says. “We are not only concerned about efficiency, but we also try to minimize the impact on the Lunar environment. We think this will become more important in the future.” Alexandre adds: “Remember that there’s more than enough regolith on the moon. The Moon’s surface is covered by 5 to 12 meters of regolith – the result of billions of years’ bombardment with tiny meteorites.”

The Moon vacuum may help if the process is also used to create pure metal powder for local use

What is regolith?

“Regolith has an intensive minerality,” Beth says, “for the rest, it is quite like stuff from Earth. The most common minerals on the Moon are the same as the ones here. But hydrates are lacking, of course, and there are no clay minerals or signs of weathering, as there is no water on the Moon. Yet, it is not very hard to imitate the stuff. There are minor differences, such as the inclusion of the fused glass materials from the micrometeorites and the lack of volatile elements – like sodium and potassium.”

Alexandre Meurisse adds that the intense radiation on the Moon also has some effects: “Grains of regolith may be covered by nanolayers of iron, which is caused partly by radiation.”

Obstacles

As far as the process is concerned, there are many difficulties to overcome. “Remember, virtually every tool or material you use for the process has to be brought from earth – at enormous expense. To be able to handle the regolith, most of which is a fine dust, with typically 50% consisting of particles smaller than 70 microns, it has to be compacted. Probably the most efficient way to do that is by sintering it into blocks, Beth Lomax explains. “At about 700 °C it will not lose much of the oxygen it contains.”

“Oxygen bonds very strongly to other elements. That is also one of our problems: every material we use has to be able to withstand being oxidised. The FFC Cambridge process, as it is called, was developed about 20 years ago for the direct extraction on Earth of titanium from titanium oxide. It is a batch process at a pressure of around one bar and a temperature of 900°, which makes it necessary to create air locks to get the material in and the oxygen out.” However, the Moon vacuum may help if the process is also used to create pure metal powder for local use – the alloys could be used to manufacture structures and components, for instance by 3D printing. “There is little chance of the metal powder reoxidising once it is outside, which usually is a problem on Earth,” Beth adds.

Future

As yet, it is unclear what the most likely power source for the FFC Cambridge Process will be. Alexandre Meurisse: “Solar energy sounds like an obvious choice, but nuclear is possible as well. It looks to me that solar power alone will not be sufficient. We don’t know yet how much power will be needed and what the efficiency will be. There still are a lot of uncertainties – the batch size, the scale of the machines etcetera”. Beth adds: “It will be necessary to balance the batch size with the smallest amount of salt needed to support the process – there is no NaCl on the Moon, so it has to be brought up from earth. But at the end of the day, decisions like that will depend on the demand for oxygen – and that again largely depends on future plans for interplanetary travel. Compared to the enormous volume needed for rocket propulsion, the amount of oxygen needed to support a settlement on the Moon is comparatively small.”

But both scientists, Beth and Alexandre, are convinced that they will witness the first manned flight to Mars, propelled with Lunar oxygen: “It’s man’s destiny.”