Closing the loop in space and on earth?

What to eat (and drink and breathe) if you go to Mars

When it will happen remains a matter of speculation, but transferring a human crew to Mars will be no easy feat. The red planet is at a distance of roughly 400 million km from the Earth, and going there will take at least 1.000 days. Getting help or provisions on the way is practically out of the question, so the mission must be self-contained. NPT talked to Heleen De Wever (VITO) and Christophe Lasseur (ESA), who have been working on the solution to this problem for years - and came across techniques that could be helpful on earth as well.

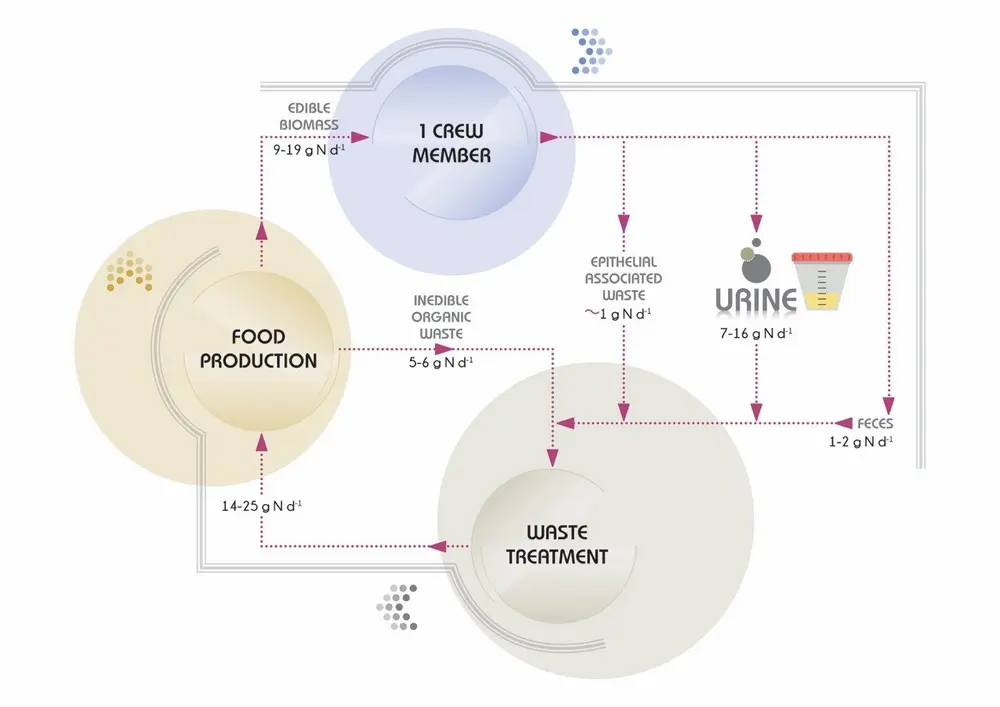

Christophe Lasseur started the conversation with some numbers: “Surviving in space requires at least 8.5 kg of consumables per day and per person, including oxygen, food, water, and some basic amenities. Multiply that by 1.000 for a trip of 1 astronaut and you get close to the maximum payload any existing single rocket can take to Mars. Obviously, we need another approach in which we maximally recycle all wastes which are generated during the mission.”

"Today, it is probably the most mature project of closed life support systems worldwide”

What does MELiSSA aim for?

Heleen De Wever: “At the moment, physicochemical processes are available to regenerate air and water by various treatments. However, these techniques consume a lot of energy and cannot produce food, which must still be resupplied from Earth. Food production can only be achieved by biological means, and the introduction of biological techniques opens a new area of solutions for other life support requirements - such as atmosphere, water and waste management. In 1989 ESA started the MELiSSA (MicroEcological Life Support System Alternative) project. Today, it is probably the most mature project of closed life support systems worldwide.”

Different functions

“MELiSSA’s life support system has a variety of functions: waste recycling e.g. treatment of black water, grey water, urine and other daily consumables, as well as production of food, water and oxygen. These functions are divided into engineered units which are first tested separately and then are integrated step by step. One of the novelties of the MELiSSA approach is that the life support system is broken down into five main processes, consisting of microbial bioreactors, microbial electrolysis cells, higher plant chambers and a crew compartment.”

Different ecosystems

Heleen continues: “Like lake ecosystems, each MELiSSA compartment is colonised by specific organisms, each providing a specific contribution to the overall processes. In a very simplified model of a lake, you can imagine that each horizontal layer is occupied by a family of micro-organisms. Starting from the bottom, you first get an anaerobic zone in which organic matter is digested in absence of oxygen and light. On top of that there will be different layers with more light, CO2 and oxygen, each containing particular life forms with their specific functions.”

“This is also challenging in terms of process design. It is a huge endeavour that has rarely been attempted in process technology”

Simplifying molecules

Christophe: “Due to the diversity in the crew’s menu, the differences in their microbiome, the crew’s stress, their activity and so on, there is a huge number of different molecules to process. Clearly, they cannot be processed by a single organism. So in a number of steps, a kind of funnel effect is created, in which complex polymers and proteins are broken down to simpler molecules like CO2, ammonium, nitrate and minerals that can be processed by one or two micro-organisms.”

Heleen: “This is also challenging in terms of process design, because we start from a dirty mix of incoming substrates. They are converted by an open mixed microbial culture to end with pure culture processes which are run under sterile conditions downstream. It is a huge endeavour that has rarely been attempted in process technology.”

Demonstration on Earth

All five compartments are multi-phase systems which are closely interconnected and depend on the exchange of nutrients, carbon sources, etc. between them. With the system running continuously over long periods of time, it is a huge challenge to simultaneously balance all flows of gas, liquid and solids with maximum recovery of carbon, nitrogen and other elements. Therefore, the tests are done step by step.

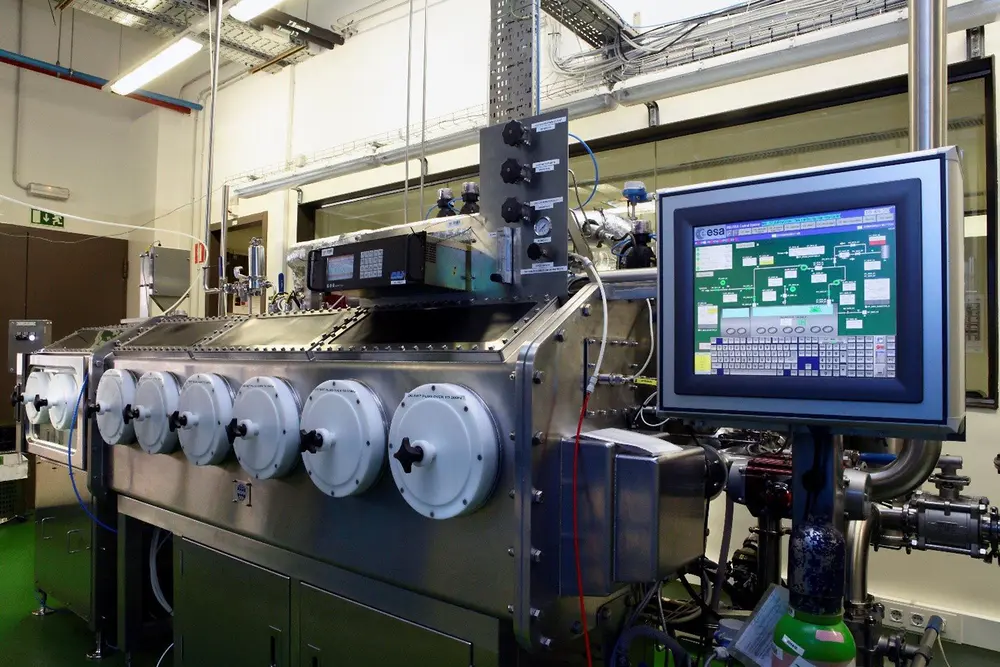

“Flight experiments cost a fortune!” Christophe says, “We try to intensively characterize, understand, model, simulate, test all conditions while on earth, keeping in mind that one day we will have to validate and check everything in space conditions.” Once operation of an individual compartment has been demonstrated, the different compartments are gradually connected in the gas, loop and solid phases. This terrestrial demonstration takes place in the MELiSSA Pilot Plant, the ESA external Laboratory located in Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). For cost and safety reasons, the demonstration is today performed with a mock-up crew of rats as a preparation phase for a future facility inhabited by humans.

From earth to space

While most investigations are currently performed on earth, parts of the MELiSSA loop have already been tested in space and there are plans to test the overall system in spaceflight in the 2030s. This is essential to prove that process performance remains robust and reliable under the extreme conditions in space.

Christophe says: “About 95% of the mission to Mars will take place in microgravity which means that multi-phase systems behave differently. For instance: liquids, gas and solids will not separate nicely as they do on earth. Moreover, living organisms are influenced by radiation. This may be less the case for micro-organisms than human beings and other mammals, but still their metabolism can evolve, creating a genetic drift which may change their performance.”

Tweaking a complex system

“Compared to eukaryotes, bacteria have impressive reconstruction capabilities, but radiation still makes the prediction and control of their behaviour much more complex,” Christophe says. “MELiSSA has gone to space only ten or eleven times already, I think. Not the entire system, of course, but only crucial parts. As a result, the system has been adapted and improved over the years although the basic idea remained – to create an assembly of different processes involving fluids, gases and solids, that we try to connect to each other to get the desired result. Improving this complex network with crosslinks and feedback mechanisms is an increasingly difficult task, because changing one process loop may have an adverse effect on the other. A single element of the network can simply not be considered apart from the others.”

Testing and learning

Doesn’t Earth’s nature already provide a perfect recycling solution for practically every output and input you can think of – maybe bulky, but very stable and efficient? Christophe’s answer was short and convincing. He said: “We get this type of comment again and again: but a holistic approach like that does not fit our way of working and thinking.” Heleen adds: “We have to follow deterministic and controllable procedures.”

Christophe: “Our assignment is very simple: to get the crew to Mars and back – alive. There’s a very narrow margin. We cannot permit unpredictable variations or uncertainties. In our research we are able to measure, describe and publish everything that happens during the tests – and we do. We learn from our mistakes. With non-deterministic systems you never know what you learned – because it may be different next time.”

Heleen nuances Christophe’s statements a bit: “Still, we use open systems, such as the anaerobic treatment of waste. In that case we do not know precisely what the function of each organism is, but we know that it works. And by increasing our knowledge we are also able to better understand natural systems.”

What about GMO?

An obvious way to focus and improve specific qualities of (micro)organisms would be by genetically manipulating them. However, MELiSSA has decided to do without genetically modified organisms. “It certainly was a point of discussion at the start of the project,” Christophe Lasseur says. “But at this moment there is a kind of agreement between the MELiSSA actors. We have not yet identified any function we are unable to perform now and which we are sure we could do with the help of GMO’s. And I don’t know if we would try it if it is not absolutely necessary, because genetically modified prokaryotes may be quite vulnerable in a high-radiation environment. Moreover, MELiSSA is a European project and in Europe there’s no agreement about the use of genetically modified organisms – especially in possible terrestrial applications of our research.”

Down to Earth

Many similarities exist between the technological approach and solutions investigated in MELiSSA and major environmental and sustainability challenges on earth. Hence it is not surprising that there have already been several terrestrial successes. Looking for organisms that could be harvested for food, the MELiSSA team came for instance across a bacterium that cuts levels of the ‘bad’ cholesterol. The bacterium is now being further investigated as a possible medicine. Other examples include the terrestrial valorization of planar thin photobioreactors as biofacades on buildings, and of grey water recycling technology at the Concordia station in Antarctica and at Roland Garros.

Heleen concludes: “But we learn in both directions. On one hand, progress made in terrestrial research on waste and water recycling, conversion and separation technology, process control etc. can benefit MELiSSA. On the other hand, the requirements and constraints of a space mission are a lot higher than you would aim for on earth. Extremely high degrees of loop closure ideally approaching 100% of resource recycling are needed in a system with small buffer capacities and fast cycling times. This pushes technology developments to the limit.”

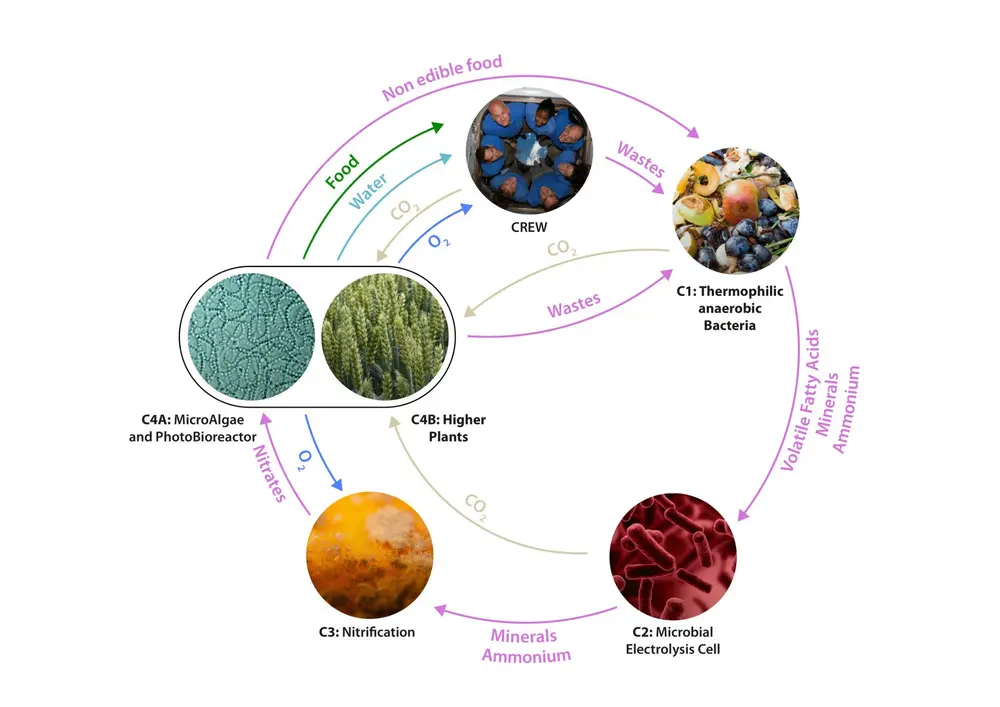

The MELiSSA closed loop life support system

Compartment I of MELiSSA (C1) or the liquefying compartment is the collection pool for human waste (i.e. feces, urea, paper) as well as the non-edible parts of the higher plant chambers (straw, roots, ...). Its essential task is to transform these waste products anaerobically to NH3, H2, CO2, volatile fatty acids (VFA) and minerals. For biosafety reasons (sanitization), as well as to improve degradation efficiency, compartment I is operated under thermophilic conditions at 55°C. For an efficient separation of the fermentation products from the biosolids, the reactor is equipped with a membrane filtration unit which also retains the micro-organisms and produces a clear cell-free permeate. The process relies on a complex and unique mixed culture, able to ferment a broad range of substrates. Fecal material and non-edible plant parts provide a continuous influx of new micro-organisms and thus determine the final microbial community composition.

As opposed to the first compartment, all downstream compartments are populated by well-defined pure or co- cultures of organisms.

In compartment II (C2), the VFA coming from the liquefying compartment are further oxidized to CO2 in a microbial electrolysis cell. Originally a single organism Rhodospirillum rubrum was used in a photoreactor to transform volatile fatty acids into CO2 and biomass, but that did not work. So this was changed to a mixed culture biofilm process, using external power inputs for the microbial oxidation.

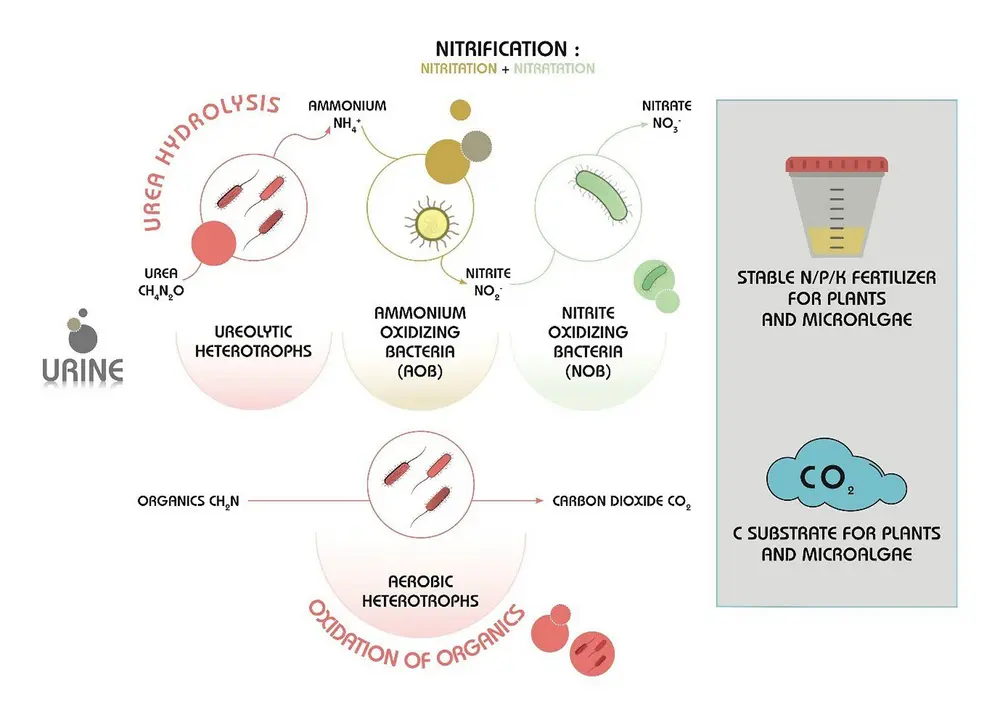

The nitrifying compartment III (C3) contains a defined co-culture of Nitrosomonas europeae and Nitrobacter winogradskyi. This consortium transforms ammonium into nitrate in the presence of oxygen. Due to the slow growth rate of nitrifying organisms and their sensitivity to adverse environmental conditions, compartment III is conceived as a fixed-bed reactor.

Nitrate and the remaining minerals are then fed into the food-producing compartment IV. This is divided into a photoautotrophic compartment (C4A) inoculated with the edible cyanobacterium Limnospira (previously Arthrospira) platensis, and a higher plant compartment (C4B) in which a variety of vegetables is cultivated. Through photosynthesis, both compartments use CO2 and produce oxygen in the presence of light, thus contributing to air revitalization.

The fifth compartment is inhabited by the crew.