PROCESS SYSTEMS ENGINEERING FOR CIRCULAR CHEMICAL SYSTEMS

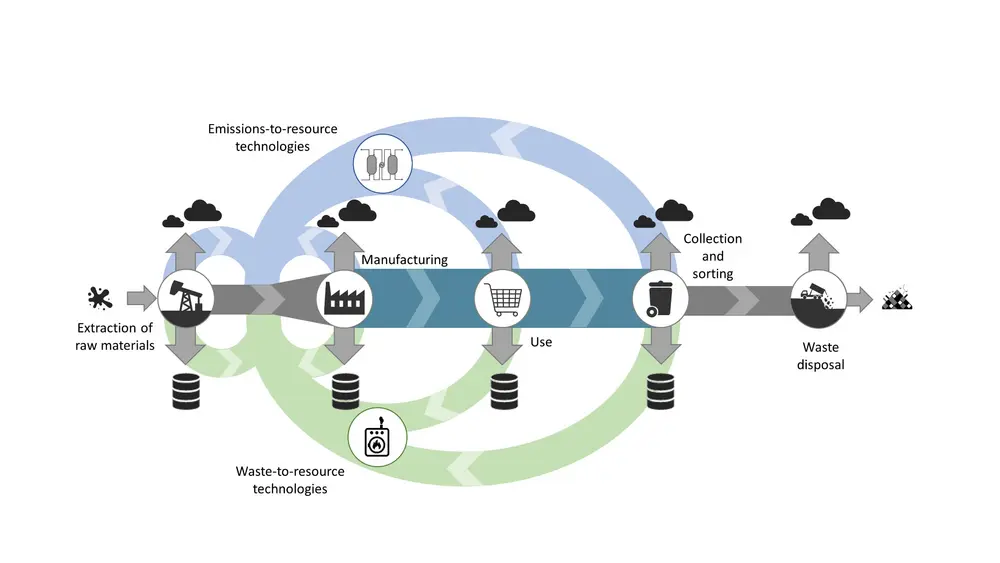

The European chemical industry will play a major role in supporting the European Green Deal to become a climate-neutral continent by 2050. Achieving carbon-neutral chemical systems will require new manufacturing patterns with circularity as the main driver of change. The circular production of chemicals relies on waste reduction and recovering resources from waste and carbon emissions through material upcycling technologies (Figure 1). To adopt these technologies, circularity has to be paired with creating economic value by sustainable means, increased process efficiencies, the use of sustainable raw materials and the transition to renewably-powered processes.

During the past decades, researchers on Process Systems Engineering (PSE) – a branch of Chemical Engineering that addresses process design, operation, and optimization – have been developing powerful decision-making tools for process industries. The systematic thinking and advanced computational tools of the PSE community can contribute to accelerate the much-needed transition to circular chemical systems.

Enabling technologies

Several technologies appear as the key enablers for circular carbon economies:

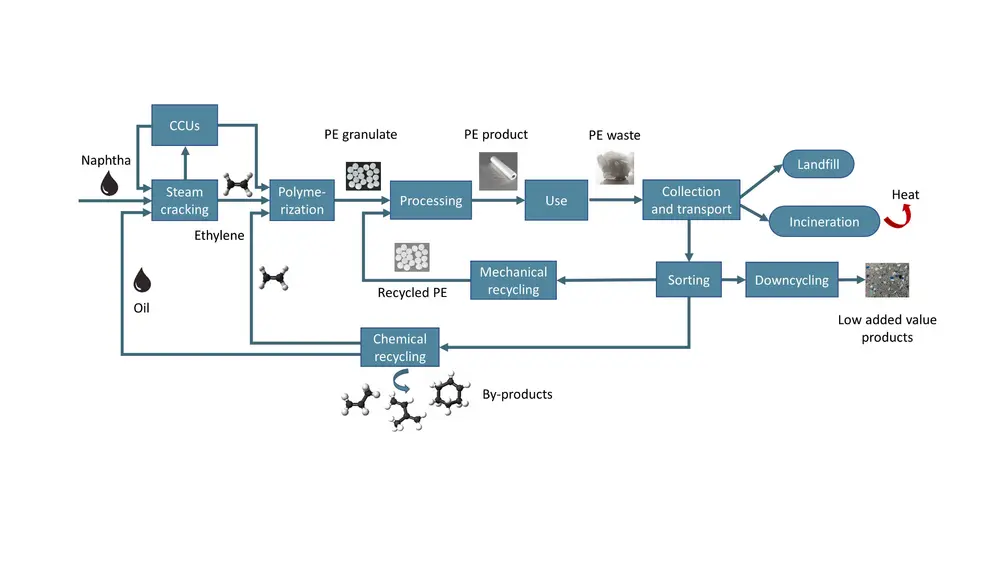

- Chemical recycling of plastic waste: In 2020, more than 19 MMT of plastic waste were generated in the European Union (Eurostat, 2021). Reaching the goal of 100% plastic repurposing will require a combination of recycling methods (an example for polyethylene in Figure 2). Chemical recycling technologies (pyrolysis, gasification, and solvolysis) can increase the circularity of plastics when mechanical recycling is not an option, by breaking down the polymers into their building blocks or oils to be refined.

- Carbon Capture and Utilization (CCU): According to the European Chemical Industry Council, the EU production of chemicals accounted for 123 MMT of CO2 emissions in 2019, a 4% of total emissions (Eurostat, 2021). CCUs can be used to capture the CO2 present in flue gas or ambient air and convert it into small molecules (i.e. carbon monoxide, formic acid, or ethylene) that can later be used in chemical synthesis. A cost-effective integration of CCU pathways (biochemical, bioelectrochemical, electrochemical, photocatalytic, photosynthetic, and thermo-catalytic processes) into chemical systems will be needed to drive the shift towards a low carbon economy of chemicals.

- Electrification of chemical operations: Another alternative to mitigate the carbon emissions of the chemical industry is substituting fossil-based energy demands by renewably-powered electricity. This includes electrically generated heat (e.g. via heat pumps or resistive heating), the use of electrolytic hydrogen, and moving from thermochemical to electrochemical conversions. The e-Refinery initiative at TU Delft is working on this energy transition towards a defossilized chemical industry.

The open questions of circularity

The inclusion of circular economy principles in chemical systems presents a plethora of new questions for chemical companies, policy makers, and researchers. Some of the challenges that we will face in the short term are:

- The scaling up of emerging technologies: Most of the enabling technologies listed above present low technology readiness levels. Research efforts have to guide the scale up to industrial sizes of promising lab-scale proofs of concept. The best practice here is to use iterative design approaches, where sizing and assessment are constantly updated with the results from the previous scale-ups.

- Moving from product-oriented to upcycling-oriented approaches: This change of perspective consists in re-evaluating the traditional design approaches where product separation was a priority due to the high-value fossil-based feedstocks. Instead, novel design approaches have to find the most efficient and sustainable options to deal with complex and impure materials.

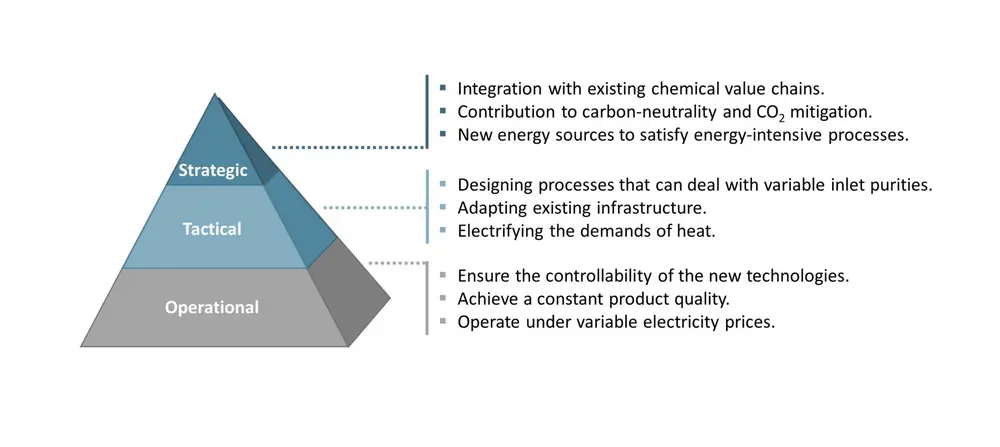

- Multi-level decision-making: While the first decisions to make are strategic or tactical (e.g. optimal pathways and integrated processes), the operability of the overall systems cannot be overlooked. Figure 3 includes some examples of the very different problems to solve at the three main decision levels.

- Satisfying the increasing energy demands with renewable energy: Upcycling technologies, and CO2 reduction in particular, are more energy-intensive than traditional synthesis. The future renewable energy systems will have to face the increased demand of the chemical industry and other sectors (e.g. electric vehicles or hydrogen production).

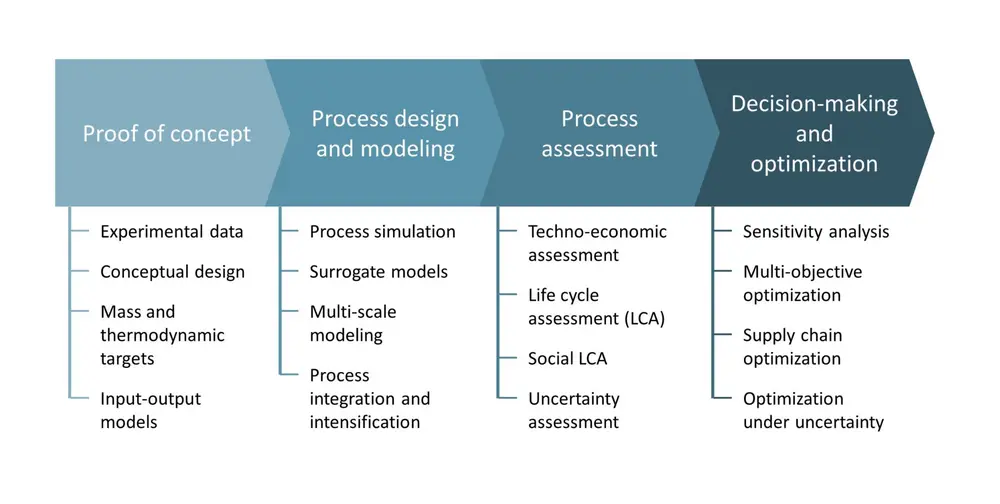

All these open questions will benefit from multi-disciplinary solutions that combine the knowledge of experimentalists, technology developers, modelers and administrations. PSE researchers can efficiently assist in the deployment of circularity thanks to their holistic problem-solving approaches and an extensive toolset (Figure 4) that covers all design phases: from the initial validation of proofs of concept to advanced decision-making.

Dr. ir. Ana Somoza-Tornos is an assistant professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). Her research focuses on developing Process Systems Engineering tools to close carbon cycles in the chemical industry via the introduction of carbon capture and utilization, and chemical recycling technologies. Her areas of expertise include process modeling and design, mathematical optimization, techno-economic assessment, life cycle assessment, and circular economy.

Read more

Somoza-Tornos et al., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 9, 3561–3572.

Somoza-Tornos et al., iScience 2021, 24, 7, 102813.